Reviews and Resonance - Vincent Valdez's "Just a Dream..." is America's rotting realities

Content warning - art depicting violence against Black and Mexican-American communities is discussed and reiterated in graphic response to artist Vincent Valdez and his gallery hosted by MASS MoCA.

In the grand room of Vincent Valdez’s “Just a Dream…” exhibit that opened at MASS MoCA in May 2025, there is no escape from the humanity in America’s cruelty. The use of light, skin, sinew, and suspense still leaves space to place the viewer in the line of fire for considering our complacency or contempt in the social, political, and cultural wars of the 21st century.

This is a deconstruction of what it meant to stand in the presence of three of these works, informed further by the extensive display of his career that went on far beyond this one room, and a pre-viewing conversation with Valdez and acclaimed writer Hanif Abdurraqib, hosted by MASS MoCA’s Denise Markonish.

None of this was comfortable to write, and I don’t anticipate it being comfortable to read. All of it, I encourage you to see for yourself, should you ever have the opportunity.

“The Strangest Fruit” (2013)

Eight Mexican-American men towered over me on their individual large-scale canvases stacked two high and four wide. Their postures varied between wrists coupled behind backs or held high and barely sustaining the head’s relationship to the body, yet no bondage, no cuffs, no tools of oppression held the bodies in place. Body language told their stories that needed no literal object to narrate on their behalf. I caught myself holding my own hands together behind my back, a common viewing posture to meander museums with, and yet an unintentionally mocked stance among these men. I pulled out my notebook, not only to proactively reflect but to deflect the discomfort of my mirroring stance.

The not-so fine line between violence and ascension, as intended by Valdez was tightly tensioned and made of more than a single string of reference. Red hues of light painted along the edges of the men’s bodies, accentuating their tattoos and defined muscles as if lit by the stained glass of a church window at sundown, though more likely the headlights of a pick-up truck in the dead of a rural night beating against the highlights of their bodies, as the blues of the shadows mocked American exceptionalism with contrasting undertones. Valdez intentionally places the noose in the viewer’s hands, the metaphorical ropes acting as the line between the lynching of Mexican-American men along the Texas-Mexico border of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the patron saints found at the lasting altars of lost loved ones.

I found myself fixated on one particular man, second from the left, on the bottom row. Arms crossed against his chest, held high, head fallen back, and legs in what could be mistaken as a leap of joy. His eyes looked out in what I could only disturbingly describe as “Épaulment”, a french term used for describing the shouldering in ballet that exposes the drama of the shoulders and neck. I winced at the reference coming all too naturally to mind and sat for an extra few moments reflecting on that discomfort while trying to hold awe of his beauty. What I believe held my gaze most was the sense of movement it evoked in a moment of death and the honesty Valdez painted into the sinew of the body’s weight, including the face’s caverns and bloated blood flow from cheek to cheekbone.

Valdez gives us both the saint and the crime to contend with, yet no place to rest a conclusion as the viewer eventually has to walk away and move along–a pained resolution to their demise. Ascension is somehow beautiful even in tragedy.

As I continued on through the gallery, I kept looking back at them, afraid to let them disappear in the rearview. The further I distanced myself, the higher they seemed to hang in the air. The title of the work begins to residually rot in the back of my throat.

“The City I” (2015-2016)

Moving along to the panoramic canvas to the left, a collective of fourteen hooded members of the KKK catch you at eye level without escape. Lit by the headlights of a Chevrolet truck to the right, these masked terrorists hold your gaze, and the proximity feels anxiously fraught. As I make my way from right to left along the painting, nearby, one parent chases down his young boy, who sprints towards the painting, demanding to touch it, while another parent whispers to his pre-teen daughter why it is such a loud statement. The awareness of viewing the painting in the company of our shared whiteness weighs heavily on the intake of information.

Aside from the eyes that peer between the holes of their hoods, hands act as windows to their souls. Aged, white (as if needed to be clarified), and frail hands gesture implied whispers and secrecy with gaudy jeweled rings creasing the skin and veins. Another holds a cell phone, the light illuminating the hands hovering above in a nearly biblical gesture of pointed command. One member clutches a notebook and pencil, indicating the organizational manner of the KKK’s agenda and infiltration of the American psyche. Centrally, a child is held under a nazi salute reached out above them. The child donned in corporate indicators like Nike shoes and holding a Pokémon toy appears eager to remove the cloth from their head while reaching for the viewer. I can’t help but consider how much innocence and reconciliation are lost to children raised on racism.

Though not so much deliberate in posturing, the scale, length, and gestures can’t be ignored in reference to Davinci’s “The Last Supper”. The sainthood of these hidden figures in image and proclamation cloak themselves behind the self-righteousness of their claims to Christianity. I wish I could delve further into this metaphor, but admittedly, my biblical knowledge is limited beyond the basics, and I don’t wish to speak too far out of turn.

“Since 1977” (2019)

When I finally chose to remove my furrowed brows of scrutiny from the blight of the Klan, I turned around 180 degrees to a new line of eyes to meet. In a series of nine canvases, seven US presidents since the time of Valdez’s birth to the project’s end in 2019 (Jimmy Carter to Donald J. Trump) are caught in moments of transitional facial reactions sourced from their terms, yet cut off at their noses. The black and white contrast and looming blackness above their hairlines keep the focus on their eyes and how their skin pushes and pulls against the sinew dictated by such strained gazes.

As time and administrations move on from left to right, the height of these men slowly declines, only slightly disrupted by Obama’s upward and exhausted face, the only to hold his energy above the viewer before plummeting us into Trump’s hairline alone - no eyes to even reference. Seven presidents, possibly seven deadly sins, I’ll let you determine who holds which transgressions, as the lowered visibility of each leader implies a decline in leadership itself.

Book-ended are two black canvases to match the center seven. The first with a blurry constitutional font reading the work title, “Since 1977”, the last pure in its darkness. Is Valdez’s punctuation a dark mark of death in America’s history? A mirror to oneself in seeing how our own faces might fall in the recent history of the United States? A gap of hope for someone to fill in the blank space better than before? Do they act as a Spanish punctuation, the question mark inverting on either end to suspend the inquiry?

Learn more and get a closer look at more of Vincent Valdez’s work at the link below:

In conversation: Vincent Valdez and Hanif Abdurraqib

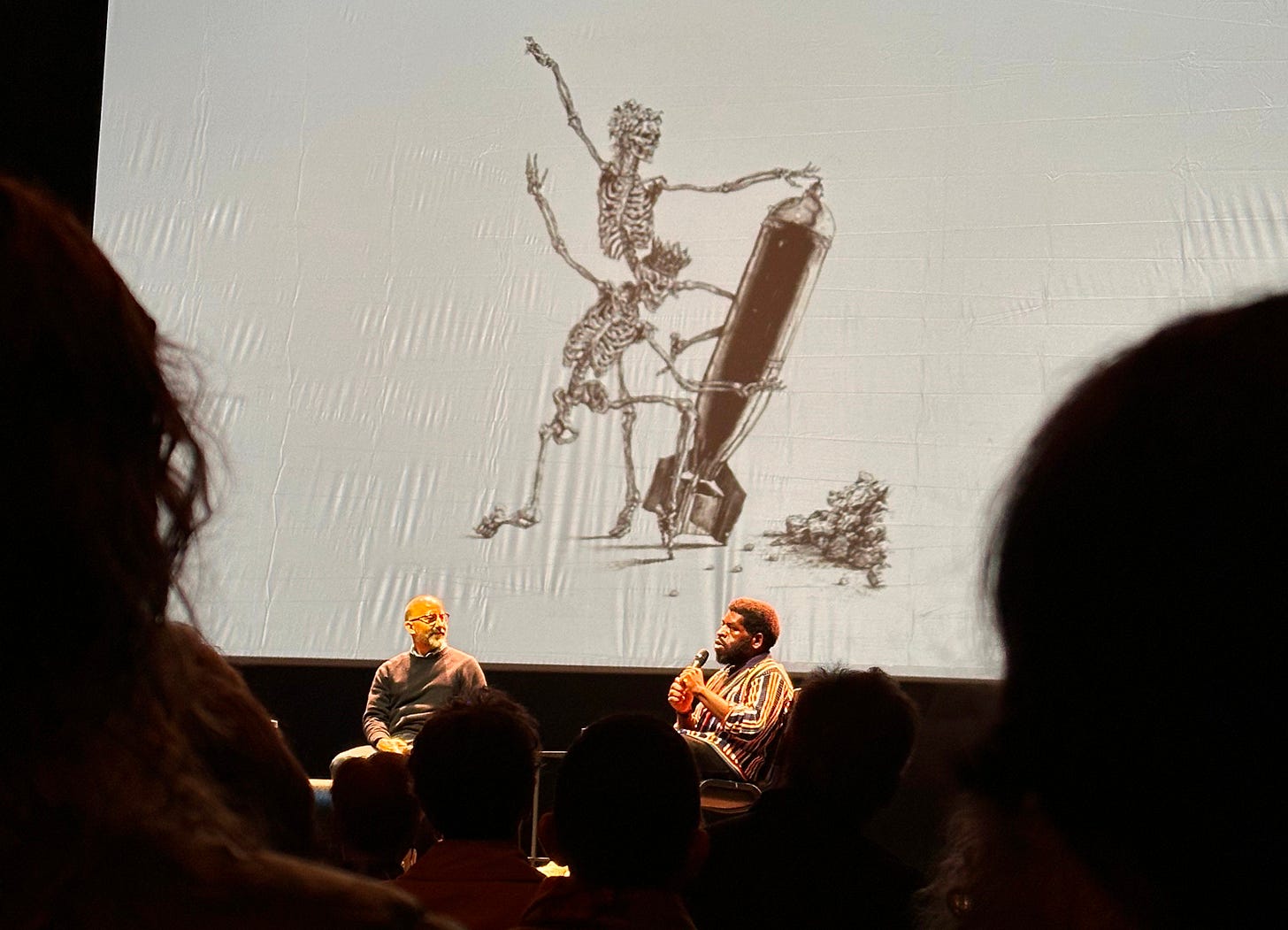

Prior to entering the gallery, DJ and I joined the artist along with poet, essayist, and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib in a live conversation. I knew a bit of Abdurraqib’s work but I admittedly didn’t know of Valdez prior to this event. The two men bonded on stage in how their different art forms speak to the missing pieces of what they seek to say in their own creative development. Above them circulated numerous of Valdez’s art over the years, which would later be seen up close throughout the gallery.

I have pages in my notebook full of quotes I hope to chew on for years to come and may reveal themselves in future dissertations - but for now I only want to note how spectacular it was so hear these two join in their love for community, their people, and their development as the key tools to their art. It was not boisterous in their acclaimed status as artists and leaned on reverence to their upbringings and community to inform where they’ve found themselves today.

After the talk, I picked up one of Hanif Abdurraqib’s books, “Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest” to be signed by him where I foolishly had nothing to say upon handing him my copy as I had not yet had the time to piece together the words of what he evoked in my mind, and I’m not sure I still do. However, as I’ve spent the past week reading through the book, I catch myself thinking back on a moment during this live conversation. He reflected on searching for the cited samples on cassette tapes in painfully small print, just to look back on what came before and contributed the art he enjoyed today.

More on that another time.

Question: How do you embody reactions to the art before you?

It may be rooted in my dancing body but I find so much physical reaction to standing among art. Not necessarily just in my nervous system but in my body language itself.

Have you ever taken stock in how you hold yourself in a gallery? Do you hold your arms behind your body or in front to retrain yourself from touching or to guard your abdomen of the gut punch being delivered by the art before you?

Do you ever think about how your face holds it’s reactions to art like any other conversation? Would you rather be honest in that visceral response or hide your true feelings like you might during an uncomfortable dinner table debate?

I’d love to hear your thoughts.

What a difficult viewing! And, what an utterly fascinating perspective you provided. Well done!