DUMPING Grounds - A guide to style x survival

How the desperate need to continue skiing while pursuing my dance career pulled the thread of my movement research for nearly ten years.

It’s worth being candid. I’ve been using this term for nearly ten years now, so if you’ve been putting up with me, my writing, my antics, and my diatribes this whole time, please forgive the lack of evolution in the phrase. There’s plenty of evolution in concept.

Foundations: the physical

From riding my longboard to class on campus at the University of Alabama to squeezing in a few ski laps between class and rehearsal at the University of Utah, I spent a lot of my college career skirting around the expectations of what was safe for my body as a dance major. There was a function to getting to class faster in the southern heat and there was joy in ripping turns down the mountain. What was often overlooked by my disapproving professors was the transfer of information in my physical body – information they were actively feeding me.

When introduced more systematically to the Bartenieff Fundamentals and theorizing the physicality of movement by way of movement research prioritized over performance, I had much more than tendus and phrase work to apply technique to.

There was a distinct lightbulb moment one day while skiing at Solitude after a morning in my modern technique class. I was dropping into my lunges (I was a telemark skier at this time, sue me), fighting the instability of the deep stance when the placement of my sternum and pelvis fell into a sort of anti-gravity between one another – a space hold. My sense of “center” floated within my torso and I became aware of my three-dimensional mobility. My legs switched positioning with ease, no burning, just euphoria. I was dancing.

Foundations: the visible

During this time, I was also re-immersing myself into the communal joy of ski film premiere season. The type of interactive experience I could only ever wish would be found in the screen dance screening experience. More on that later.

I quickly picked up on the physicality of the featured skiers. Namely, Karl Fostvedt who I have to credit for a piece of this beginning after he commented about my transition to “dancing on skis” while sitting in an Environmental Justice class together.

Nice dude.

Even more so, a very stylistic and talented skier. During a few film premieres that featured his segments, I started to pick up on my ability to recognize him quickly on screen among other notable freeskiers of the 2010’s, even amidst the montages of various athletes, kit variations, and most notably, the lack of opportunity to identify someone by their face. The more films I watched, the better I recognized each skier strictly by their movement style.

The core inquiry:

How does one have control over their movement style while actively hucking themselves off a wedge of trucked-in snow built in the middle of an abandoned building in Detroit on two planks?

You don’t.

I’m not saying skiers don’t actively embellish their movement to stylize it, but I do know that the choice to do so at such a high-risk moment can sometimes be a life-and-death decision.

No one starts skiing by chucking themselves off cliffs just like dancers don’t start with intricate floor work or the Black Swan Variation. Everyone starts with basics, builds upon them, masters them, and then expands. That sense of risk and scale evolves as you grow through the development until the cliff and 32 fouettes have more to do with tying up technical loose ends than overcoming the whole movement.

But the cliff can kill you – and I’m admittedly more interested in that.

Action sports often include a more extreme sense of risk whether it’s speed, incline, obstacles, or gravity – meanwhile, art, such as dance, is often spoken of through a more stylized lens. So, as we watch action sports like skiing, snowboarding, skateboarding, climbing, etc. my ears perk up when I hear talk of an athlete’s style.

What are others seeing when they identify someone’s “style”?

A theory on risk:

Style x survival is all about risk. When the body is put into a situation that poses a threat, it is going to source from all its developed knowledge to activate instinct. This is why learning to fall is just as important as learning to stay upright.

Risk has a way of stripping the body of performance. Regardless of caliber, whether it’s driven by a formal competition or trying to show off under the chairlift, in the thick of risk - the body will (read: should) choose itself over the ego’s claim to fame - that is if it’s been fed the safety handbook and a healthy dose of trial and failures.

What I’m saying is that style becomes inherent, rather than performed when the motion is laced with a little fight or flight response. The style is designed by survival.

What defines risk?

Risk as defined by Merriam-Webster is as follows:

risk: noun

: possibility of loss or injury : peril

: someone or something that creates or suggests a hazard

The foundation of style x survival began with backflips off cliffs but the expansion of risk is where it lies today. I don’t demand notions of risk to be life and death threats in this research. Risk may determine ease of daily tasks or questioning the unknown.

Here are the many ways I have continued to inquire about risk’s impact on the physicality of style over the years:

Adaptive sports - I work often with adaptive athletes including climbers, skiers, cyclists, and beyond as a volunteer through various programs. The inherent knowledge that is programmed into bodies living in a world not adapted to their disabilities is incredibly insightful. Adaptive athletes and artists demonstrate creativity and alternate solutions that are greatly informed by a world that unfortunately also puts them at risk for lack of adaptive accommodations. Disabled bodies are immeasurably intelligent bodies.

Cultural dance - Lately I’ve spent some time considering how cultural dance both in ancestral and current developments root in the need to survive risk. Those risks may be referencing a spiritual nature to provide life-giving necessities like bountiful harvests and ample rain – similarly, the human need for connection is often evolved through social dance, derived from culture itself.

Sustainable daily functions - fine-tuning one’s awareness to their kinesphere provides fluid mobility through daily life. How tuned into our surroundings we are keeps us aware of daily risks no matter of high or low consequence; such as colliding with another person while in passing, making quick-snap decisions to toss or catch an item, or determining the safety of a loved one’s embrace in the absence of risk.

Risk as you may initially consider it. Thrill seekers, adrenaline addicts, and pushing the limit of possibility. This is where the neurological intel would be fascinating to cross-reference with the theories above. Since reading about professor Marvin Zuckerman’s psychological research about the Sensation Seeking Scale from Heather Hansman’s book Powder Days, I have wanted to integrate the SSS scale into this movement research.

The development thus far

Over the past 10 years, I have been a professional dancer and choreographer, marketing director, photographer, filmmaker, volunteer, and community member within the centralized goal of access to movement.

I have had the opportunity to see dance within institutions, companies, legacies, and even more so – outside of dance itself. My experiences have not been exclusively in performance but have been a gathering of data and intel to inform the success of dance. The research of style x survival has brought solutions to my various workforces.

I’m interested in looking outside of dance to promise its future – merging the intelligent body’s reverence across movement types. Risk can be found somewhere in every action and celebrating, preparing, and navigating those variations is what will produce a style only known to one body no matter the act.

So where do we go from here?

Well, that’s what makes me want to crawl out of my own skin to discover. It feels like a desperate question that cannot be googled. I want to propel this research through social, technical, and cultural conversations. There are a number of desires as to how I want to expand my understanding of this theory.

For one, I would be thrilled to have access to body mapping technologies, particularly in understanding how adaptations change relative alignments to action. Adaptive climbers are a top interest here as the function of “beta” challenges what an observer’s solution to the next move on the wall would be vs. the alternative adaptations made by a body that may be limited in reach, mobility, or limbs.

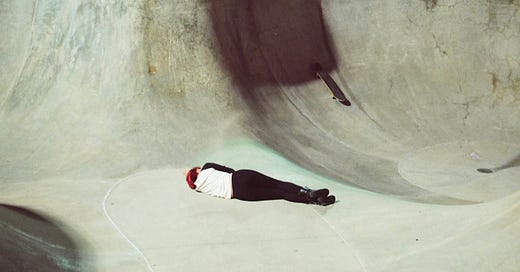

I want to challenge creative developments in choreographic movement further through physical and abstract spaces. By referencing external barriers, textures, and spatial design, movement is generated by external factors conversing with intuition – potentially overriding indulgence. These may include developed processes of my own or referencing already established techniques such as William Forsythe’s “6 Collapsing Points” methods or tools that have found their way to me. This tennis ball exploration that my Instagram feed recently fed me by Fábio Alcântara really scratched the style x survival itch and is something I’d love to respectfully adapt in my research.

Choreographic, photographic, and video creations will continue to be a critical part of this investigation all while I’ll be seeking to strip the performance nature itself from the body in favor of the survival function.

Finally, I want to better understand how this can inform the temporary able-bodied lives we all face as investments in aging, access, and rehabilitation. I’m looking at what can be improved upon to train our bodies for intuitive responses in the face of risk, encourage daily adaptations, and cause improved shared value of access and adaptive mobility.

There is a case for even the flick of a finger to be a dance, thus dance holds the power of acting as a centralized research hub for informing all movement. I want to leverage that power, celebrate the artistry found in everybody, and extend those discoveries to the betterment of daily life in partnership with medicine, policy, product design, and more.

All because I really didn’t want to give up skiing.

Thank you for indulging in these questions. If you have stories or reflections on the experience of style x survival, I am always open to hearing about them.

Written by Tori Duhaime, photographer and movement artists

Oh I love the way you talk about movement.